Belmondo: The role of his life

PostED ON 05.10.2015 AT 10:50AM

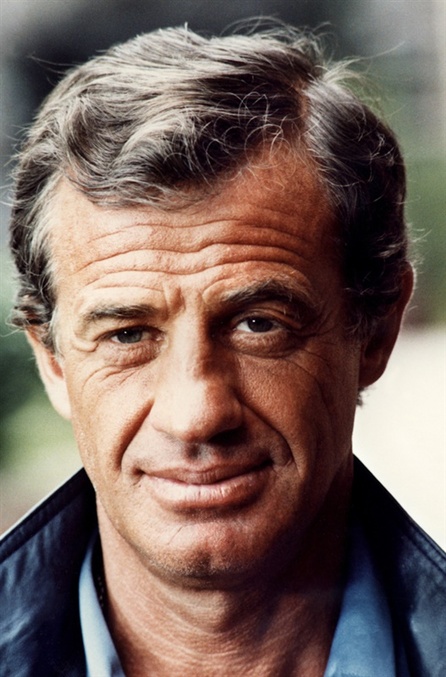

DOCUMENTARY - A son pays a modest tribute to his father, who, just as modestly, evokes what has been nonetheless an extraordinary career. From Rome to Paris, from Rio de Janeiro to Villerville (Calvados), Paul Belmondo films Jean-Paul Belmondo on the shooting sites that have marked his career. The vintage Ford Mustang he drives with Charles Gérard, his supporting actor and (practically) forever pal, sets the tone: the top has to be down because the weather must always be sunny, like memories of youth… Even if John Paul still has speech difficulties, a result of the stroke he suffered in 2001, he has fully retained his lucidity and his memory. His trademark laugh ("eh, eh, eh...") recurs throughout the documentary, like musical notes that resonate in the ninety-odd films he has made in six decades of the cinema. At age 82, despite his trials and tribulations, Belmondo still loves life and has not lost a bit of his sense of humor.

Watching excerpts again that have punctuated this journey, hearing anecdotes that characterize him as the gentleman actor - preferring soft polite irony to rehashing ill-will on another "sacred monster," a friend in twilight decline- we are struck by Belmondo's elegance: never taking himself too seriously, even while working with serious resolve as the dramatic actor, the clown or the stuntman. And we conclude that, as a man and as an actor, "Bebel," as the French call him, has aged better than others.

There is of course Belmondo's physique. Although not quite attaining the stature of a handsome hunk, it nonetheless impresses by its agility, its flexibility, its direct gaze, its classy way of exuding slight detachment. Cliché? Difficult in any case not to notice the invariably high "modernity" of his first undertakings: in Breathless (1960), obviously, then in Pierrot le fou (1965), where his nonchalance and irony are the stylistic "revolution" assigned by Godard. In Italian films as well, like Vittorio De Sica's Two Women (1960) - presented at this year's festival in homage to Sophia Loren - or Bolognini's The Lovemakers (1961), his restraint is well suited to the darkness of these tragedies marked by neorealism. In France, Belmondo jumps enthusiastically into new roles: he plays a master of sensitivity in The Big Risk by Claude Sautet (1960) before slipping perfectly into the sleek cinema of Melville with Léon Morin Priest (1961), Doulos: The Finger Man (1962), or Magnet of Doom (1963), despite tension.

Afterwards, in the 70s and 80s, it will be anything and everything, literally. Belmondo makes dramas, good and not-so-good criminal or cop flicks (leaving behind the suit in favor of the new modern police "uniform" of jeans and the bomber jacket), slapstick movies and great comedies (by De Broca) which the critics pan until they are brought up to speed thanks to homages paid by "youngsters" like Dujardin and Michel Hazanavicius in OSS 117: Lost in Rio (2009). We also find him hanging from ropes, from helicopters in flight, running on the roofs of the Paris Metro or the Opera… "Before Jacky Chan did his own stunts, it was Belmondo who was doing them," proclaimed Tarantino, admiring the "supercoolness" of Bebel at the Lumière festival tribute in 2013. But when the son asks his father about taking all these risks, Jean-Paul Belmondo simply answers: "I'm not afraid of heights."

…And behind this remark, we believe we catch a glimpse of the confidence Belmondo may have in himself, the confidence he gives to others, to life. In the end, the documentary, far from lamenting with nostalgia for a bygone era, provides an enjoyable perspective through encounters with those who knew, loved or admired him. It paints the picture of a cultivated man who never feared the critics of the "general public," an actor who has always been completely committed (sometimes misguided), without cynicism. He has managed to keep the most precious elements of childhood, endeavoring to foster vitality and buoyancy. The message may be indispensible for the times we're living in: Don't be afraid.