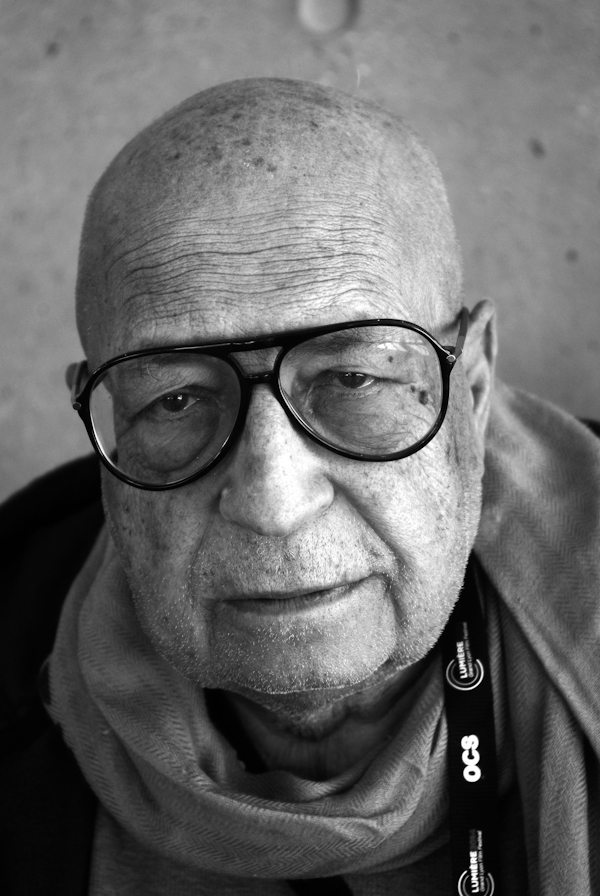

Pierre Rissient

The illuminating enthusiast

PostED ON 29.09.2015 AT 11:20AM

PORTRAIT - It was Clint Eastwood, with his trademark brevity, that best defines what Pierre Rissient is in the cinema world: "Mr Everywhere." After all, Eastwood, the last giant of Hollywood classics, knows he's had a debt to this unclassifiable yet essential international figure for the last sixty years. It was the Frenchman, incidentally, who worked to tear off the "cowboy/tough cop" label, allowing Eastwood's directorial talents shine through, celebrated with the very first Lumière Award in 2009.

The two men couldn't help but get along. Because if Pierre Rissient was indeed "everywhere" in the cinema galaxy, he was still deeply passionate and still a maverick (the latter word dear to Philippe Garnier, originally defined as animals who didn't follow the pack). "Maverick" is indeed apt in this case; from the beginning in the fifties, the cinephile programmer of the Mac Mahon Theater in Paris defended the likes of Walsh, Losey, Preminger and Lang, directors at the time ignored by some or deemed "too commercial "by others. Rissient was also keen on Night and the City (1950) by Jules Dassin (a generally despised film noir), seeing existential angst worthy of Woyzeck, the play by Georg Büchner. Rissient said it served as his first lesson about the need to think and judge for himself (preferring for example, Cottavafi to Antonioni with no apologies; daring to declare Citizen Kane "overrated" compared to other works by Orson Welles such as The Magnificent Ambersons). But Dassin's feature flick also led to the realization that genre films, be they thrillers or Westerns, could also be considered major works, a point Pierre Rissient has never ceased to defend, even in regards to literature (Gallimard's Série Noire or crime novels by Rivages Editions).

Rissient was Godard's assistant on Breathless, became a formidable press officer (along with Bertrand Tavernier), a distributor, director (only two films, but 1982's Five and the Skin highly deserves be rediscovered) and an executive producer for Ciby 2000 or Pathé. He was an especially gifted international talent scout: Eastwood, but also Schatzberg, Coppola, Tarantino, Australian Jane Campion, Iranian Abbas Kiarostami, Hong Kong's King Hu for A Touch of Zen (1970), or Filipino Lino Brocka for Insiang (1976)… His support of many artists has often led to a selection at the Cannes Film Festival.

Whether extoling the treasures of silent film (on which he is inexhaustible), or defending the most recent film by a Zainichi Korean which profoundly affected him (Unforgiven by Sang-il Lee) or insisting on rereading Alfred Hayes, an American novelist and screenwriter discovered late in life, Pierre Rissient appreciates, discusses, becomes passionate, fights. Always in the name of cinema or literature, he will at least avoid posthumous ridicule, unlike those in the 1970s who dictated good taste in the name of ideological considerations bogged down by semiotic or structuralist jumble.

Of course, this somewhat uncouth man has not made only friends in the industry, and the close relationships he was able to maintain (with Losey, Lino Brocka or Jane Campion) have sometimes suffered. Yet they all express the immense respect for his "eye" and his uncompromising convictions. Todd McCarthy, the great American film critic and former editor of Variety, made Rissient a subject of a documentary (Man of Cinema, 2007); young cinephiles from "So Film" represented him in a BD as a kind of omniscient uncle; and the Telluride festival baptized a film theater "Le Pierre." Today, Benoît Jacquot, Pascal Mérigeau and Guy Seligmann pay him homage in Gentleman Rissient, a film screened for the first time at the Lumière festival. Since the theme is all about cinephile passion of heritage and transmission, it seems only natural to pay tribute to this incomparable "transmitter," Pierre Rissient.

P.S.

---

Pierre Rissient, Gentleman Rissient by Benoît Jacquot, Pascal Mérigeau and Guy Seligmann (2015, 58min)