Two films by Larisa Shepitko

PostED ON 07.10.2015

ANALYSIS - On July 7, 1979, Andrei Tarkovsky wrote about his friend in his diary: "Yesterday was the funeral of Larisa Sheptiko and five members of her group. A car accident. All killed instantly. So suddenly, that not one of them had adrenaline in the blood. It seems that the driver fell asleep at the wheel. It was early morning. Between Ostachkovo and Kalinin."

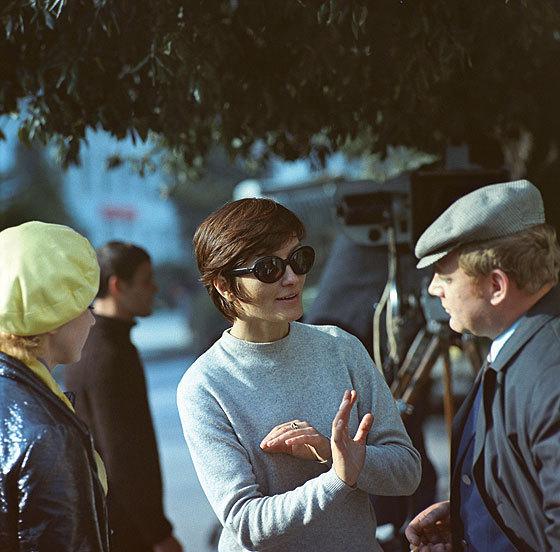

Deceased on July 2, 1979, Larisa Shepitko, aged 41, had made only five films. Her beauty allowed her to begin an acting career before turning her hand towards directing, attending classes at the VGIK (Moscow Institute of Cinema) taught by fellow Ukrainian Alexander Dovzhenko*. She would always adhere to the lessons of her mentor: "Dovzhenko taught us to remain faithful to ourselves, to trust our feelings, to defend our ideas. I did not know then how difficult that was." In fact, Shepitko's cinema continues to question the place of the singular, the value of commitment and the sense of total submission to the collectivist logic that governed Soviet society. Alongside Kira Mourotova, Elem Klimov or Otar Iosselani, she pushed the possibilities towards a more openly rebellious cinema than her glorious predecessors. In this respect, at a certain point, Larisa Shepitko could be associated with the movement known as the "Thaw period" of "Thaw cinema," inspired by the Western nouvelles vagues of the time.

Wings (1966)

In Wings (1966), however, the "thaw" is on hold: although Brezhnev has succeeded Khrushchev almost two years beforehand, the curtain remains iron, the skies remain leaden. Like in The Ascent (1977), the salvation of the heroine is yet to come from the skies of heaven, although the expression here is literal, as Nadezhda is a former fighter pilot, a fervent Stalinist with a glorious and dramatic past.

Discovering this film now has all the effect of donning a suit, having forgotten to take it off the hanger. Everything is stiff, gray and formal. The sweet and dignified face of Nadezhda is vaguely androgynous, like a more sentimental version of Christine Ockrent. As soon as a faint smile is discernable, it must be hastily wiped away, like a tear. In the four corners of the frame, always perfectly composed, someone seems to be watching in the shadows. So one sunny morning, Nadezhda becomes friendly with a waitress and ends up dancing with her in the empty café. They enjoy a split second of carefreeness, when, nearly instantly, they see men glued to the windows, like to the walls of a fish tank, with their gaping mouths and bulging eyes… But more often, Nadezhda is seen strolling along the corridors of the institution, stiff as an Easter candle waiting for the flame to be relit. Following her war wounds which kept her on the ground, she becomes a school Director and Member of the City Council. Thus, a person of note. A woman who is also - emphatically - alone. As a war heroine, she is an icon displayed in the museum of the town, but when she returns home, her daughter announces her intention to marry a 37 year-old divorced man, without even bothering to ask her approval.

"You should envy me instead of embarrassing me," she says, distraught. Yet Nadezhda resolves to get to know her future son in-law and is confronted by a group of artists and intellectuals who seem unreceptive to official propaganda. She brings a cake and wine that she intends to share with them, forcing herself to appear cheerful: "Young people - why are you so solemn? Play your boogie-woogie!" But is a saxophone that completes the scene, crooning beat music, as if borrowed from a Robert Frank film. Beyond the forced good mood, the two generations and the two conceptions of existence clash, irreconcilably, the first in a long line of conflicts. At another point, she searches for a rebellious student who has run away. When she knocks on the door, a babushka opens it to a thin crack. "Why don't you open the door, grandmother? What are you afraid of? - Did you not see the chain? I cannot open the door- the chain would stop me." It is through this kind of vaguely absurd metaphor of the climate of oppression that turns the sky into an unattainable ceiling. Nadezhda is halfway through her life; she thinks of her only love, a hero too, who died in battle. How to overcome this, even during a pacified time, when boredom weighs on every step of her administrative burden? During an audition for school show rehearsals, she questions a colleague by asking, "What's a synonym for the word 'initiative?'" - to which the colleague answers, "Initiation."

One day, no longer able to tolerate it, she takes advantage of a moment of distraction of her former comrades and slips into the cockpit of an airplane to feel her heart beating fast again. Here, she races away, her plane spiraling straight down, then shooting up straight for the clouds. The film stops. Did she remain in heaven?

Dovzhenko's advice will be heeded and Larisa Sheptiko will never give up defending her convictions in the face of censorship, which fails to stop her last film, The Ascent, from being shown in Berlin. Fortunately, the film receives the highest award, "The Golden Bear," thereby making all the absurd attempts to muzzle her work ludicrous, handing her revenge and bringing her triumphant international recognition.

The Ascent (1977)

"The action of the film takes place in Belarus during WWII. The Germans take prisoner two Soviet partisans, who learn they are to be hanged. One of them, Rybak, cracks and agrees to collaborate; the other, Sotnikov, calmly faces death."

From the beginning of the film, the Russian army is not presented to us as a compact mass trying to escape the German threat but as an accumulation of individuals seized by the cold, panic and hunger. In a starkly contrasting black and white, everyone is on watch. The soldiers recall the memory of a farm nearby which could contain food and send Sotnikov and Rybak, who try to reach it, but with great difficulty. Snow acts as a deletion of the territory - implicitly making the fight for the maintaining the fronts futile - man is but a brittle piece of charcoal on the white page, in danger of crumbling at any moment.

The farm finally appears but the Germans have already passed. Sotnikov is wounded, yet Rybak forces him to continue. Their salvation is bound to be at the end of their march, thwarted by this white, clinging compact powder, in which they are knee-deep. The animal in them, the ultimate survival instinct, controls these two puppets coated in white like Christmas snowmen. There is also a real snowman built by children in the yard of another farm where the two of them find refuge.

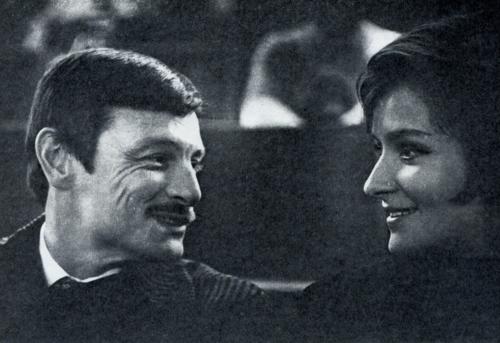

A woman lives there alone with her three children. Too soon, a German patrol discovers them hiding in the attic, and barbarity sets in. The Germans make them all prisoners and lead them to the nearest garrison town where they undergo the tyranny of a police commissar with stylish sadism and morbid murder. Here, we recognize the great Anatoly Solonitsyn, Tarkovsky's formidable Andrei Rublev.

Thrown into the cellar, Sotnikov now addresses Rybak as "Koyla" and a heated argument ensues. "How can you give in? We are soldiers! Do not swim in that shit, you cannot cleanse yourself of it!" The consciousness of the educated man, his morality more heroic than any patriotism, thus opposes Sotnikov to Koyla, when the latter begins scheming to collaborate with the enemy.

Koyla's morals consist only of his desire for survival, the vital instinct that has kept him- and Sotnikov- alive. As the opposition between them becomes drastic, black invades the screen. The original white of the snowy plains now is now hit with the seeping anthracite of cell bricks, where, awaiting the final morning when they will be hanged, cluster together among the rats, and the black of night.

"What we must remember is that each of us is ruled by one and the other character; our entire life is a mixture of these two elements, Good and Evil, and we are back to Dostoevsky," says Larisa Sheptiko in an interview with the monthly Écran in March of 1978. Marcel Martin says, "Shepitko mentions rereading Dostoyevsky at a time when she was going through a serious existential crisis and it is certain that there is something of Myshkin in the character of Sotnikov, a typical Russian mysticism in this symbolic face-to-face of the hero and the traitor "(The Soviet Cinema, L'Age d'Homme, 1993).

In the morning, they are led to the gallows. Only Koyla, the traitor, escapes the rope. The others who did not want to give away the positions of the Russian army and the activity of partisans are gathered "to perform their sacrifice on a hill, a veritable Calvary, where the gallows are erected before the assembled town. The religious overtones are striking. (...) Let us say, rather, the overtones of a Christian culture." By the gift they make of their lives, they "rise above themselves, it is their ascension," Ginette Gervais wrote in Jeune Cinéma in 1977.

A survivor but not alive, numb with shame and cold, Koyla is a dead man and he knows it. He shuts himself in the lavatory, desperately trying to hang himself with his belt, but fails. It does not matter- he is dead. He collapses to his knees, crying, and looks up to heaven.

Emile Breton, in his Dictionary of Films (Seuil, 1990), speaks of a "disconcerting" film, shaped as a "Christian parable about redemption experienced by two Soviet partisans." We assume then, that it is this purported Christian interpretation of the film that so displeased the censorship authorities.

Pierre Collier

* Earth, by Alexander Dovzhenko, will be screened on Wednesday, October 14 at the Institut Lumière as part of the carte blanche selection by Martin Scorsese.

---